最新一期的ORIENTATIONS杂志出版,八篇文章

Durga Mahishasuramardini shrine

1. Analysis of a Pala–Sena Metal Durga Mahishasuramardini Shrine

David Nalin

This article analyses the composition, structure and style of a unique sculptural masterpiece from medieval northeast India—a metal shrine of the Hindu goddess Durga killing the buffalo demon Mahishasura (Fig. 1). According to the Hindu tradition, the demon had terrorized the universe and created an existential threat to the gods. He had already defeated them individually, and was only overcome when they fused together to form Durga, who embodied all of their various powers. As the demon crept up on her in the guise of the buffalo, Durga, her multiple arms each bearing a different weapon, decapitated the beast and, grabbing the demon by his hair as he emerged from the buffalo’s neck, speared him in the chest. In the task of dispatching the demon, Durga is typically assisted by her lion vahana (‘vehicle’), which, in different versions, bites either the demon’s elbow, knee, toe or buttocks....

2. Three Licchavi Period Sculptures Under One Roof: The Solomon Family Collection of Nepalese Art (Part Two)

Gautama V. Vajracharya

Female figure with a parrot perched on her wrist

Following on from Part One, which discussed a Nepalese Licchavi period (c. 200–879) inscribed copper statue of the Newar ancestor god Indra in the Solomon Family Collection (see Orientations, March/April 2020, pp. 86–95), this article presents two previously unpublished Licchavi sculptures in the collection: a four-faced Shiva lingam and a female figure with a parrot perched on her wrist....

3. Who is that Human at Shimao? China’s Ancient Belief in Metamorphic Power

Elizabeth Childs-Johnson

Head of the dragon in the burial shroud in Figure 7

The carved block in Figure 1, which features a massive image of what appears to be a primarily human form with extended arms in displayed position to left and right of a frontal face and abbreviated body, is one of a number of sandstone relief sculptures recently excavated from architectural edifices at the late Neolithic citadel site of Shimao in Shenmu county, Shaanxi province, China. The site dates to 2200–1800 BCE, the very end of the late Longshan cultural phase (also called Longshan tradition or Longshan Age/era; c. 3000–1900 BCE) and beginning of the dynastic phase known in later histories as Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE). The finds are exciting corroborative evidence that early belief in metamorphic imagery was not limited to a scale of art that includes only ritual paraphernalia such as bronzes, lacquers, ceramics, ivories or jades, but rather is found on a massive scale decorating panels of wall structures within, in this case, a palatial hilltop fortress in the far northwest part of the East Asian Heartland (in other words, ‘China’ before it became ‘China’ in the historical period; ...

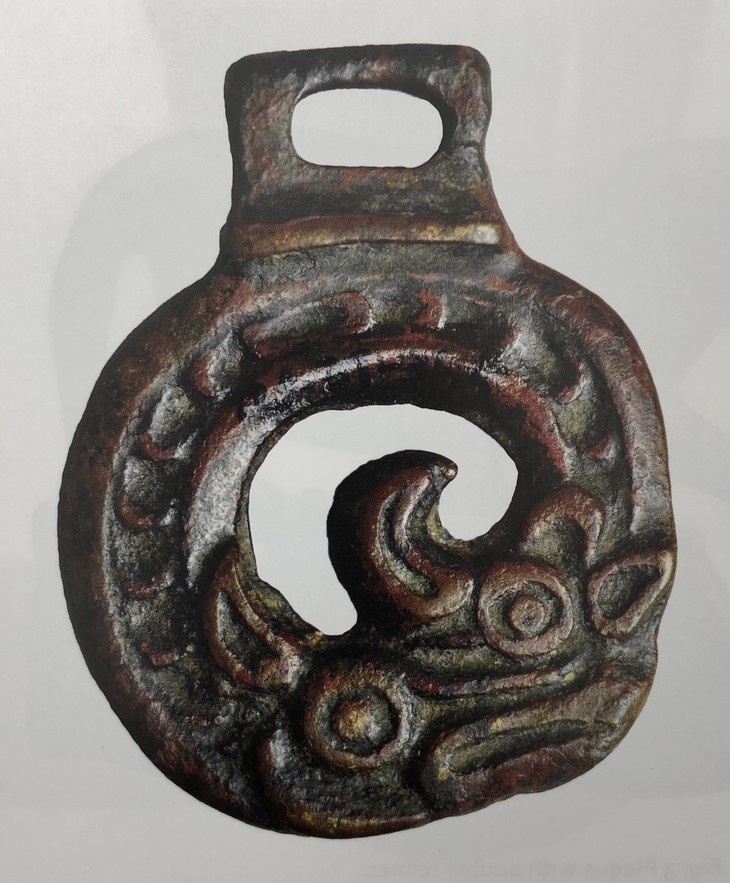

4. ‘Animal Style’ at the Penn Museum: Conceptualizing Portable Steppe Art and its Visual Rhetoric

Petya Andreeva

Harness ornament with coiled fantastic animal

Nestled in the desert sands of the Yellow river bend in north China, the Ordos region in today’s Inner Mongolia encompasses a cultural zone with a long history of intense cultural interaction. Once home to a mixture of nomadic and sedentary populations, it is now representative of China’s endeavours towards fast-paced urban development. The sparsely populated, skyscraper-filled Kangbashi district in the present-day city of Ordos boasts a large public square crowded with references to the region’s past. Monumental bronze sculptures illustrating visual narratives of the Mongol empire (1206–1368) define the spatial parameters, from images of the birth of Chinggis Khan (r. 1206–27) to the victories of his army across Eurasia....

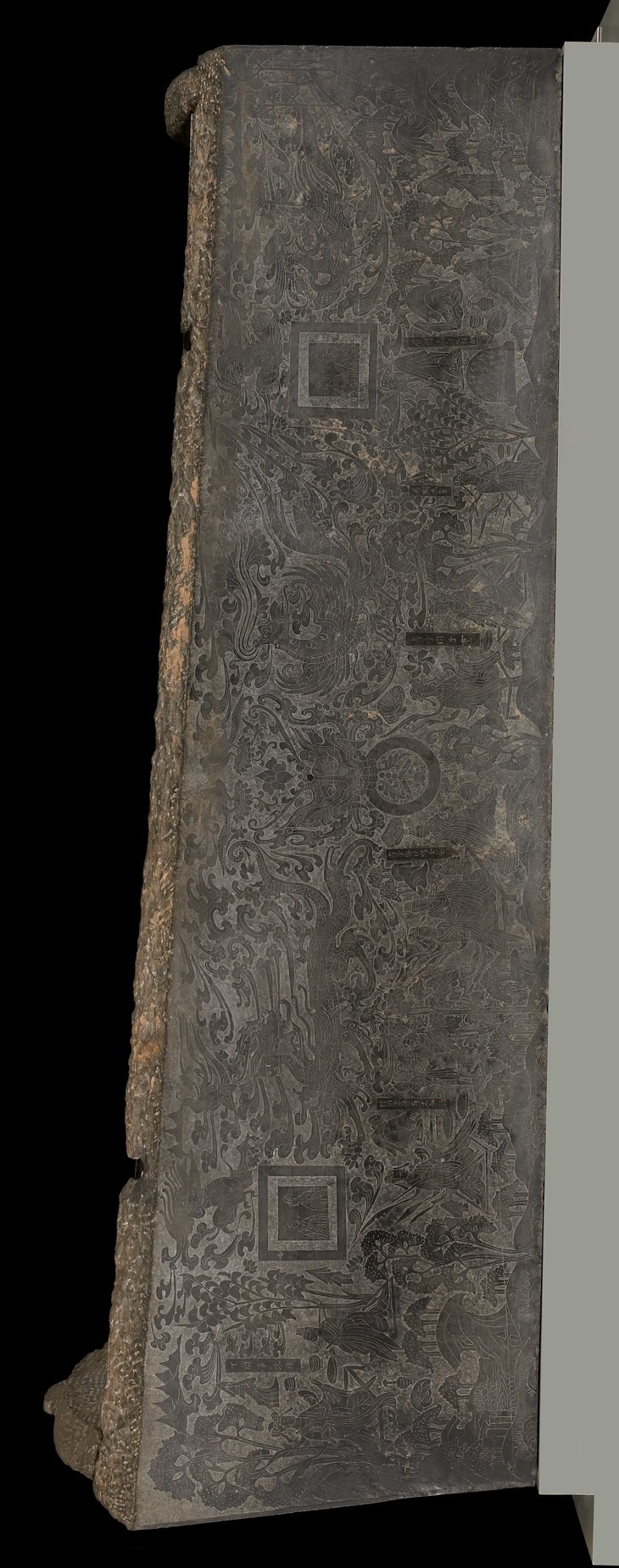

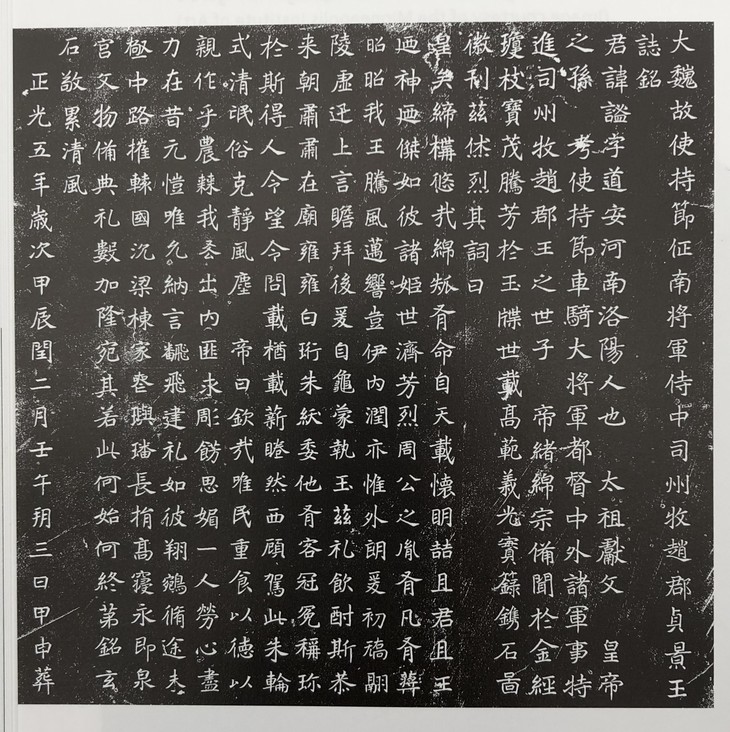

5. Recovering the Honour of a Royal General: The ‘Yuan Mi’ Sarcophagus Reattributed

Jin Xu 徐津

'Yuan Mi' sarcophagus

The ‘Yuan Mi’ sarcophagus (hereafter, ‘the Mia sarcophagus’) is a stone coffin dating to the 520s that is decorated with intricately engraved imagery (Figs 1 and 1a). It is one of the most important extant examples of stone carvings from early medieval China (220–581). Acquired by the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) in 1946, it is among the best-known Chinese artworks on display in the United States. The sarcophagus belongs to a group of late Northern Wei (386–534) mortuary stones uncovered in Luoyang (in Henan province) in the early 20th century, mostly under unknown circumstances (Huang, 1987). As far as decorated coffins are concerned, the Mia sarcophagus has long been considered the only one whose owner can be identified with any certainty; most scholars believe the sarcophagus was made for the tomb of Yuan Mi, a Northern Wei prince who died in 523 and was buried in Luoyang the following year.....

Yuan Mi's epitaph

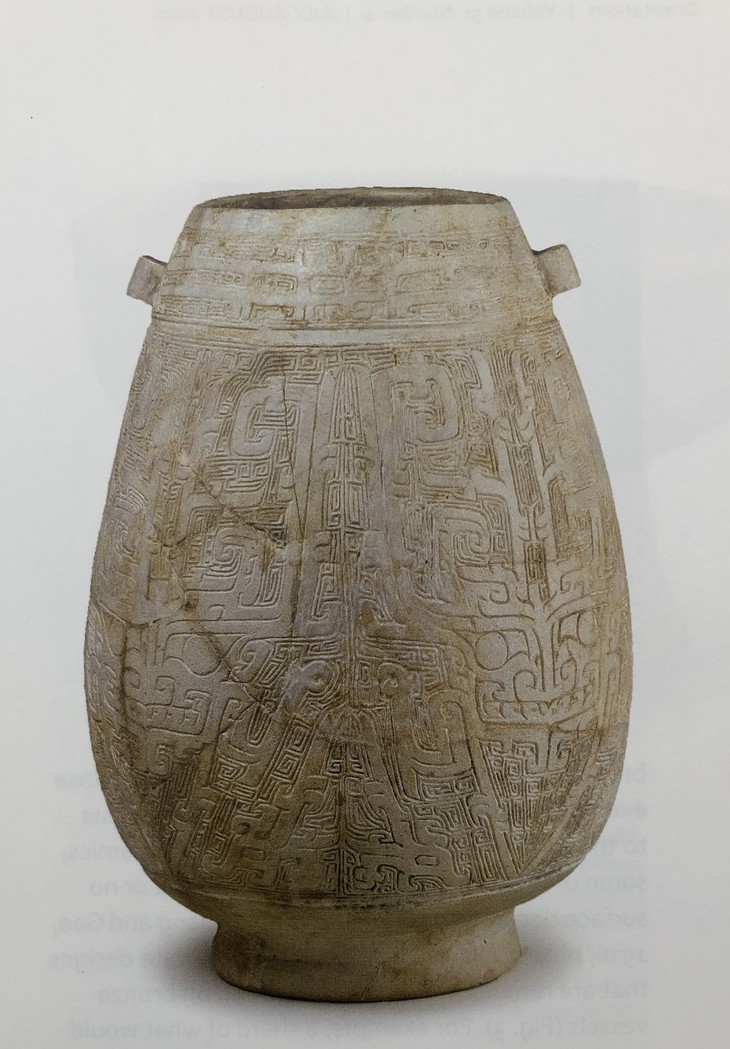

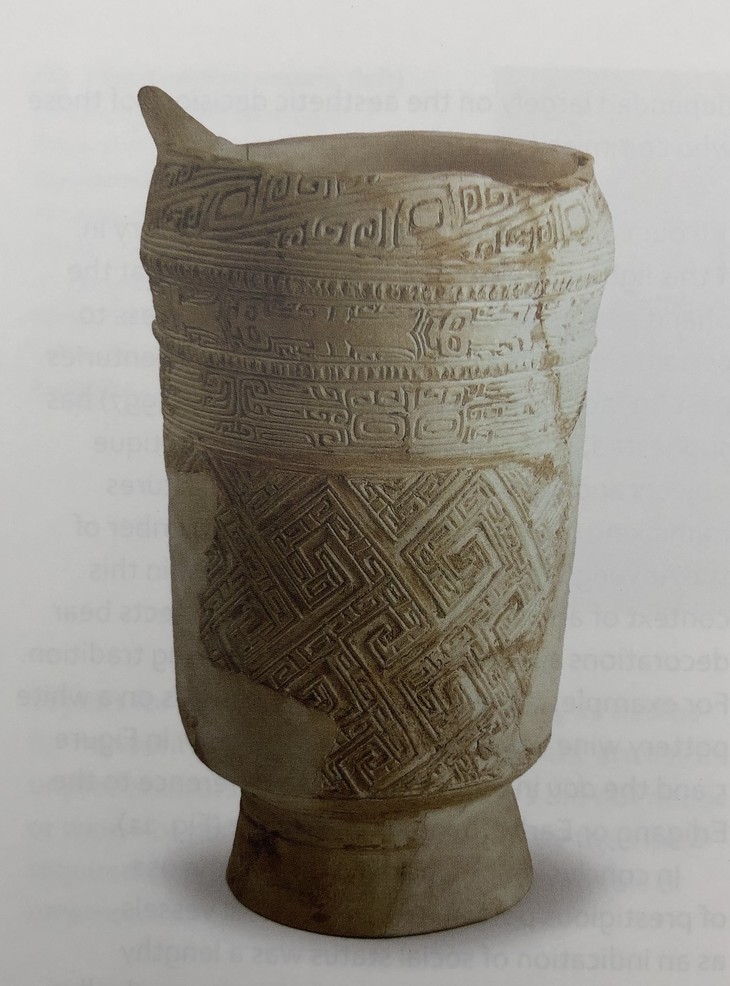

6. White Pottery of Anyang in the Late Shang Period

Alice Cheng

Lidded jar

Flask

Wine vessel

When metallurgy first emerged in the Central Plains in early China, most notably at the site of Erlitou (c. 1900–1500 BCE) in Yanshi, Luoyang, in today’s Henan province, most bronze objects took the forms of existing clay vessels (Bagley, 1999, pp. 139–42 and 158–65). This tendency continued in the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), entering its peak in the Late Shang (c. 1250–1046 BCE). An enormous number of bronze vessels from Anyang (also in Henan), the major dynastic site of the Late Shang regime, share the same forms as their clay prototypes. The decision to cast most bronzes in forms used in pottery, instead of as tools or weapons, sets the Shang and its succeeding bronze cultures apart from all others around the world. The intricate relationship between bronze and pottery in the Shang period is further revealed when one examines the piece-mould bronze-casting method, which used clay to create the core and mould sections (Bagley, 1990; Nickel, 2006). In this article, I will explore this relationship and consider several questions that have seldom been raised—for example, was prestigious pottery still produced and used after the emergence of bronze vessels? If so, what were its functions and social roles in relation to bronze vessels?

...

7. Transplanting Suzhou: The Huntington’s Garden of Flowing Fragrance (Liu Fang Yuan)

Phillip E. Bloom

On first consideration, the existence of a 17th century Suzhou-style Chinese garden in contemporary Southern California might seem paradoxical. After all, the differences in climate are great—Suzhou, in China’s Jiangsu province, is a humid, subtropical city, while Southern California, on the west coast of the United States, is a dry, Mediterranean region—and the differences in culture are even greater. Indeed, if 17th century Suzhou was renowned as a centre of the lettered arts and associated crafts, then today’s Southern California is often perceived as its opposite: a place where pop culture thrives and high culture withers.

However, Southern California is also home to one of the largest populations of people of Chinese heritage in the US. Moreover, the region houses a number of remarkable cultural institutions, one of which—The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino—shares much in spirit with the scholar-merchants’ gardens of Ming dynasty (1368–1644) Suzhou. Founded in 1919 by the railroad and real estate magnate Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927), The Huntington holds world-renowned collections of British and American archival materials, books and art; in addition, more than 15,000 species of plants (and 28,000 cultivars) flourish in its sixteen gardens, making it one of the most diverse botanical collections in the world....