人间天堂 英文原版小说 This Side of Paradise 进口书籍 英文版

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 68 件 |

商品详情

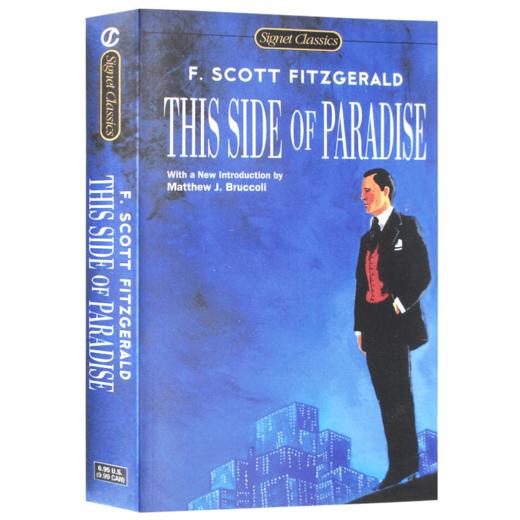

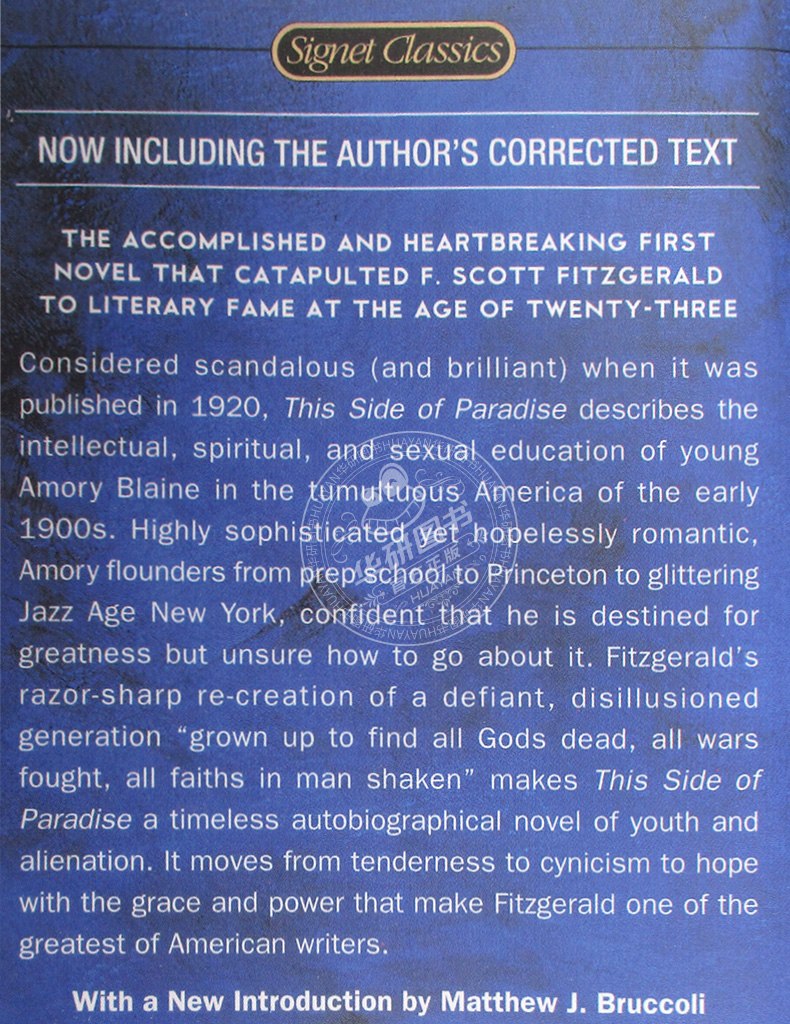

书名:This Side of Paradise人间天堂

难度:Lexile蓝思阅读指数1070L

作者:F. Scott Fitzgerald

出版社名称:Signet Classics

出版时间:2006

语种:英文

ISBN:9780451530349

商品尺寸:10.6 x1.9x 17.3 cm

包装:简装

页数:288 (以实物为准)

This Side of Paradise《人间天堂》是菲茨杰拉德的处女作,也是一部划时代的作品。它的问世奠定了菲茨杰拉德作为“爵士时代”的魁首和桂冠诗人的地位。在《人间天堂》中,菲茨杰拉德通过对艾莫里“幻想——追求——破灭”这一历程细致入微的描绘,“将青年人狂热追求‘美国梦’的幻想和注定要破灭的这一主题淋漓尽致地表现了出来”。

本书为Signet Classics推出的英文原版,由Matthew J. Bruccoli作序,内容完整无删减,书本小巧便携。

THE ACCOMPLISHED AND HEARTBREAKING FIRST NOVEL THAT CATAPULTED F. SCOTT FITZGERALD TO LITERARY FAME AT THE AGE OF TWENTY-THREE

Considered scandalous (and brilliant) when it was published in 1920,This Side of Paradisedescribes the intellectual, spiritual, and sexual education of young Amory Blaine in the tumultuous America of the early twentieth century. Highly sophisticated yet hopelessly romantic, Amory flounders from prep school to Princeton to glittering Jazz Age New York, confident that he is destined for greatness but unsure how to go about it. Fitzgerald’s razor-sharp re-creation of a defiant, disillusioned generation “grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken” makesThis Side of Paradisea timeless autobiographical novel of youth and alienation. It moves from tenderness to cynicism to hope with the grace and power that make Fitzgerald one of the greatest of American writers.

NOW INCLUDING THE AUTHOR’S CORRECTED TEXT

With an Introduction by Matthew J. Bruccoli

This Side of Paradise《人间天堂》讲述二十世纪二十年代,是美国史上一个特殊的年代。那个喧腾年代,国家呈现出一种不寻常的面貌。小说主人公艾莫里·布莱恩,便是那个年代迷惘、彷徨和失望的年轻人的代表。他英俊而家境优渥,他的雄心勃勃、意气昂扬、受挫失望、悲观迷惘,都是菲茨杰拉德本人和他同时代年轻人的真实写照。他们沉溺于漫长的、日以继夜的梦幻之中,总有一天必然要走出来,走进那个肮脏的、灰色的旋涡中去追求他们的爱情和骄傲。

Increasingly disillusioned by the rejection slips that studded the walls of his room and his on/off engagement to Zelda Sayre, Fitzgerald began his third revision of the novel that was to become This Side of Paradise.

The story of a young man’s painful sexual and intellectual awakening that echoes Fitzgerald’s own career, it is also a portrait of the lost generation that followed straight on from the First World War, 'grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken' and wanting money and success more than anything else.

弗朗西斯·斯科特·基·菲茨杰拉德,美国小说家。1896年9月24日生于明尼苏达州圣保罗市,曾考入普林斯顿大学,后因身体欠佳,中途辍学。1920年出版长篇小说《人间天堂》,从此名声大噪,1925年《了不起的盖茨比》问世,奠定了他在现代美国文学史上的地位,成了20年代“爵士时代”的发言人和“迷惘的一代”的代表作家之一。其他作品有《美丽与毁灭》《夜色温柔》《最后的大亨》(未完成)。

F. Scott Fitzgerald(1896–1940) was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, and educated at the Newman School and at Princeton.This Side of Paradise, his first novel, was published in 1920 and transformed him virtually overnight into a spokesman for his generation and a prophet of the Jazz Age. That same year, he married Zelda Sayre, and the two became America’s most celebrated expatriates, dividing their time between New York, Paris, and the Riviera during the twenties. Fitzgerald’s most famous novel,The Great Gatsby, was published in 1925, andTender Is the Nightin 1934. After Scott and Zelda were forced by money and health problems to return to the United States, Fitzgerald became a writer for Hollywood movie studios. He died while working on his unfinished novel of Hollywood,The Last Tycoon. His other works includeFlappers and Philosophers(1920),The Beautiful and Damned(1922),Tales of the Jazz Age(1922),All the Sad Young Men(1926), andTaps at Reveille(1935).

The country’s leading authority on F. Scott Fitzgerald for more than five decades,Matthew J. Bruccoliwas born in the Bronx in 1931. He was Emily Brown Jefferies Distinguished Professor at the University of South Carolina and author or editor of more than fifty books, including the standard Fitzgerald biography,Some Sort of Epic Grandeur. Among his other subjects were Ernest Hemingway, John O’Hara, Thomas Wolfe, James Gould Cozzens, and Ross Macdonald, and he edited the letters and notebooks of Vladimir Nabokov. He died in 2008.

Book One

The Romantic Egotist

Amory, Son of Beatrice

Amory Blaine inherited from his mother every trait, except the stray inexpressible few, that made him worthwhile. His father, an ineffectual, inarticulate man with a taste for Byron and a habit for drowsing over the Encyclopedia Britannica, grew wealthy at thirty through the death of two elder brothers, successful Chicago brokers, and in the first flush of feeling that the world was his, went to Bar Harbor and met Beatrice O’Hara. In consequence, Stephen Blaine handed down to posterity his height of just under six feet and his tendency to waver at crucial moments, these two abstractions appearing in his son Amory. For many years he hovered in the background of his family’s life, an unassertive figure with a face half-obliterated by lifeless, silky hair continually occupied in “taking care” of his wife, continually harassed by the idea that he didn’t and couldn’t understand her.

But Beatrice Blaine! There was a woman! Early pictures taken on her father’s estate at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, or in Rome at the Sacred Heart Convent—an educational extravagance that in her youth was only for the daughters of the exceptionally wealthy—showed the exquisite delicacy of her features, the consummate art and simplicity of her clothes. A brilliant education she had—her youth passed in renaissance glory, she was versed in the latest gossip of the Older Roman Families; known by name as a fabulously wealthy American girl to Cardinal Vitori and Queen Margherita and more subtle celebrities that one must have had some culture even to have heard of. She learned in England to prefer whiskey and soda to wine, and her small talk was broadened in two senses during a winter in Vienna. All in all Beatrice O’Hara absorbed the sort of education that will be quite impossible ever again; a tutelage measured by the number of things and people one could be contemptuous of and charming about; a culture rich in all arts and traditions, barren of all ideas, in the last of those days when the great gardener clipped the inferior roses to produce one perfect bud.

In her less important moments she returned to America, met Stephen Blaine and married him—this almost entirely because she was a little bit weary, a little bit sad. Her only child was carried through a tiresome season and brought into the world on a spring day in ninety-six.

When Amory was five he was already a delightful companion for her. He was an auburn-haired boy, with great, handsome eyes which he would grow up to in time, a facile imaginative mind and a taste for fancy dress. From his fourth to his tenth year he did the country with his mother in her father’s private car, from Coronado, where his mother became so bored that she had a nervous breakdown in a fashionable hotel, down to Mexico City, where she took a mild, almost epidemic consumption. This trouble pleased her, and later she made use of it as an intrinsic part of her atmosphere—especially after several astounding bracers.

So, while more or less fortunate little rich boys were defying governesses on the beach at Newport, or being spanked or tutored or read to from “Do and Dare,” or “Frank on the Mississippi,” Amory was biting acquiescent bell-boys in the Waldorf, outgrowing a natural repugnance to chamber music and symphonies, and deriving a highly specialized education from his mother.

“Amory.”

“Yes, Beatrice.” (Such a quaint name for his mother; she encouraged it.)

“Dear, don’t think of getting out of bed yet. I’ve always suspected that early rising in early life makes one nervous. Clothilde is having your breakfast brought up.”

“All right.”

“I am feeling very old today, Amory,” she would sigh, her face a rare cameo of pathos, her voice exquisitely modulated, her hands as facile as Bernhardt’s. “My nerves are on edge—on edge. We must leave this terrifying place tomorrow and go searching for sunshine.”

Amory’s penetrating green eyes would look out through tangled hair at his mother. Even at this age he had no illusions about her.

“Amory.”

“Oh, yes.”

“I want you to take a red-hot bath—as hot as you can bear it, and just relax your nerves. You can read in the tub if you wish.”

She fed him sections of the “Fêtes Galantes” before he was ten; at eleven he could talk glibly, if rather reminiscently, of Brahms and Mozart and Beethoven. One afternoon, when left alone in the hotel at Hot Springs, he sampled his mother’s apricot cordial, and as the taste pleased him, he became quite tipsy. This was fun for a while, but he essayed a cigarette in his exaltation, and succumbed to a vulgar, plebeian reaction. Though this incident horrified Beatrice, it also secretly amused her and became part of what in a later generation would have been termed her “line.”

“This son of mine,” he heard her tell a room full of awe-struck, admiring women one day, “is entirely sophisticated and quite charming—but delicate—we’re all delicate; here, you know.” Her hand was radiantly outlined against her beautiful bosom; then sinking her voice to a whisper, she told them of the apricot cordial. They rejoiced, for she was a brave raconteuse, but many were the keys turned in sideboard locks that night against the possible defection of little Bobby or Barbara...

These domestic pilgrimages were invariably in state; two maids, the private car, or Mr. Blaine when available, and very often a physician. When Amory had the whooping-cough four disgusted specialists glared at each other hunched around his bed; when he took scarlet fever the number of attendants, including physicians and nurses, totalled fourteen. However, blood being thicker than broth, he was pulled through.

The Blaines were attached to no city. They were the Blaines of Lake Geneva; they had quite enough relatives to serve in place of friends, and an enviable standing from Pasadena to Cape Cod. But Beatrice grew more and more prone to like only new acquaintances, as there were certain stories, such as the history of her constitution and its many amendments, memories of her years abroad, that it was necessary for her to repeat at regular intervals. Like Freudian dreams, they must be thrown off, else they would sweep in and lay siege to her nerves. But Beatrice was critical about American women, especially the floating population of ex-Westerners.

“They have accents, my dear,” she told Amory, “not Southern accents or Boston accents, not an accent attached to any locality, just an accent”—she became dreamy. “They pick up old, moth-eaten London accents that are down on their luck and have to be used by some one. They talk as an English butler might after several years in a Chicago grand opera company.” She became almost incoherent— “Suppose—time in every Western woman’s life—she feels her husband is prosperous enough for her to have—accent—they try to impress me, my dear—”

Though she thought of her body as a mass of frailties, she considered her soul quite as ill, and therefore important in her life. She had once been a Catholic, but discovering that priests were infinitely more attentive when she was in process of losing or regaining faith in Mother Church, she maintained an enchantingly wavering attitude. Often she deplored the bourgeois quality of the American Catholic clergy, and was quite sure that had she lived in the shadow of the great Continental cathedrals her soul would still be a thin flame on the mighty altar of Rome. Still, next to doctors, priests were her favorite sport.

“Ah, Bishop Wiston,” she would declare, “I do not want to talk of myself. I can imagine the stream of hysterical women fluttering at your doors, beseeching you to be simpatico”—then after an interlude filled by the clergyman—

“but my mood—is—oddly dissimilar.”

Only to bishops and above did she divulge her clerical romance. When she had first returned to her country there had been a pagan, Swinburnian young man in Asheville, for whose passionate kisses and unsentimental conversations she had taken a decided penchant—they had discussed the matter pro and con with an intellectual romancing quite devoid of soppiness. Eventually she had decided to marry for background, and the young pagan from Asheville had gone through a spiritual crisis, joined the Catholic Church, and was now—Monsignor Darcy.

“Indeed, Mrs. Blaine, he is still delightful company—quite the cardinal’s right-hand man.”

“Amory will go to him one day, I know,” breathed the beautiful lady, “and Monsignor Darcy will understand him as he understood me.”

- 华研外语 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...