Collins 正版 潜水钟与蝴蝶 英文原版 The Diving-bell and the Butterfly 突破生命的传奇 姚晨 陈绮贞推荐 英文版进口英语书籍

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 7 件 |

商品详情

书名:The Diving-bell and the Butterfly 潜水钟与蝴蝶

作者:Jean-Dominique Bauby让-多米尼克·鲍比

出版社名称:HarperPerennial

出版时间:2002

语种:英文

ISBN:9780007139842

商品尺寸:12.9 x 1 x 19.8 cm

包装:平装

页数:144

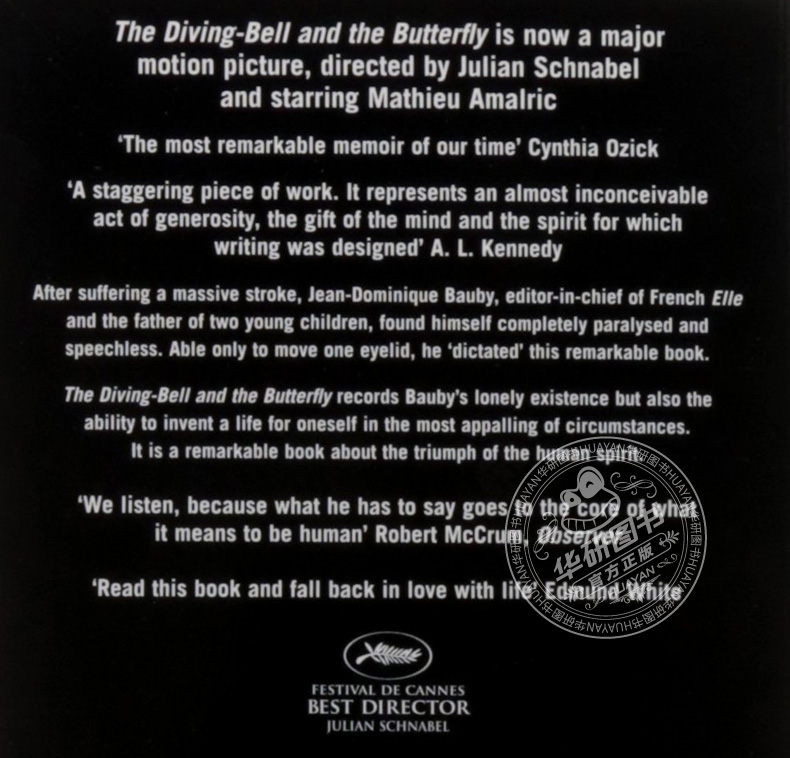

The Diving-bell and the Butterfly《潜水钟与蝴蝶》是让-多米尼克·鲍比1997年创作的散文,讲述了他本人在经历中风、瘫痪,只有左眼可以活动后,通过眨动左眼与他人沟通,记录自己的所思所想的故事。2007年,根据《潜水钟与蝴蝶》改编的同名电影一举摘得戛纳电影节大奖。

★姚晨、陈绮贞、五月天阿信、桂纶镁、李威感动推荐!

★一本突破生命极限的传奇杰作

★被命运囚禁于沉重的肉身,只有一扇眼球大的窗口,却用尽力气,向世界发声

★听到某个需要的字母,全身瘫痪的他就眨一下左眼……这样写下一个字母、一个词、一句话,写下这本书。

★“我的肉体沉重如潜水钟,但内心渴望像蝴蝶般自由飞翔。除了我的眼睛外,还有两样东西没有瘫痪:我的想象,以及我的记忆。只有想象和记忆,才能令我摆脱潜水钟的束缚。”

★“一本给绝望者以光明的不可思议的书,一本让人类变得更加坚强的书,一本伟大的书。”——《纽约时报》

“Locked-in syndrome: paralysed from head to toe, the patient, his mind intact, is imprisoned inside his own body, unable to speak or move. In my case, blinking my left eyelid is my only means of communication.” In December 1995, Jean-Dominique Bauby, editor-in-chief of French ‘Elle’ and the father of two young children, suffered a massive stroke and found himself paralysed and speechless, but entirely conscious, trapped by what doctors call ‘locked-in syndrome’. Using his only functioning muscle— his left eyelid— he began dictating this remarkable story, painstakingly spelling it out letter by letter. His book offers a haunting, harrowing look inside the cruel prison of locked-in syndrome, but it is also a triumph of the human spirit. The acclaimed 2007 film adaptation, directed by Julian Schnabel, won Best Director at Cannes and was nominated for the Palme d’Or.

让-多米尼克·鲍比

1952年生。在巴黎求学,后任记者数年。

1991年,出任法国《ELLE》杂志总编辑。

1995年12月8日,突发闭锁综合征。20天后,他苏醒过来时,全身已瘫痪,只剩左眼皮能够自主活动,这成了他与世界交流的唯一通道。当友人念到某个需要的字母时,他就眨一下左眼,这样写下一个字母、一个词、一句话……写下这本书。

1997年3月9日,《潜水钟与蝴蝶》出版两天后,鲍比去世。

蝴蝶飞出了潜水钟。

In 1995, Jean-Dominique Bauby was the editor-in-chief of French Elle, the father of two young childen, a 44-year-old man known and loved for his wit, his style, and his impassioned approach to life. By the end of the year he was also the victim of a rare kind of stroke to the brainstem. After 20 days in a coma, Bauby awoke into a body which had all but stopped working: only his left eye functioned, allowing him to see and, by blinking it, to make clear that his mind was unimpaired. Almost miraculously, he was soon able to express himself in the richest detail: dictating a word at a time, blinking to select each letter as the alphabet was recited to him slowly, over and over again. In the same way, he was able eventually to compose this extraordinary book.

By turns wistful, mischievous, angry, and witty, Bauby bears witness to his determination to live as fully in his mind as he had been able to do in his body. He explains the joy, and deep sadness, of seeing his children and of hearing his aged father’s voice on the phone. In magical sequences, he imagines traveling to other places and times and of lying next to the woman he loves. Fed only intravenously, he imagines preparing and tasting the full flavor of delectable dishes. Again and again he returns to an “inexhaustible reservoir of sensations,” keeping in touch with himself and the life around him.

Jean-Dominique Bauby died two days after the French publication ofThe Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

让-多米尼克·鲍比,1952年生,在巴黎求学。后任记者数年。1991年,出任法国《ELEE》杂志总编辑。1995年12月8日,突发脑中风。1997年3月9日,去世。

Jean-Dominique Bauby was born in 1952. He was the Editor-in-Chief of French Elle Magazine. He died on 9 March 1997.

The Wheelchair

I had never seen so many white coats in my little room. Nurses, orderlies, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, neurologist, interns and even the department head – the whole hospital had turned out for the event. When they first burst in, pushing the device ahead of them, I thought it meant that I was being ejected to make room for a new patient. I had already been at Berck a few weeks, and was daily drawing nearer to the shores of awareness, but I still could not imagine any connection between a wheelchair and me.

No one had yet given me an accurate picture of my situation, and I clung to the certainty, based on bits and pieces I had overheard, that I would very quickly recover movement and speech.

Indeed, my roving mind was busy with a thousand projects: a novel, travel, a play, marketing a fruit cocktail of my own invention. (Don’t ask for the recipe; I have forgotten it.) They immediately dressed me. ‘Good for the morale,’ pronounced the neurologist in sententious tones. And in truth I would have been pleased to trade my yellow nylon hospital gown for a checked shirt, old trousers and a shapeless sweater – except that it was a nightmare to put them on. Or rather to watch the clothes manipulated, after endless contortions, over these uncooperative deadweight limbs, which serve me only as a source of pain.

When I was finally dressed the ritual could begin. Two attendants seized me by the shoulders and feet, lifted me off the bed and dumped me unceremoniously into the wheelchair. I had graduated from being a patient whose prognosis was uncertain to an official quadriplegic. They didn’t quite applaud, but they came close. My caretakers made me travel the length and breadth of the hospital floor to make certain that the seated position did not trigger uncontrollable spasms, but I was too devastated by this brutal downgrading of my future hopes to take much notice. They had to place a special cushion behind my head: it was wobbling about like the head of one of those African women upon removal of the stack of rings that has been stretching her neck for years. ‘You can handle the wheelchair,’ said the occupational therapist with a smile intended to make the remark sound like good news, whereas to my ears it had the ring of a life-sentence. In one flash I saw the frightening truth. It was as blinding as an atomic explosion and keener than a guillotine blade. They all left.

As three orderlies laid me back down, I thought of movie gangsters struggling to fit the slain informer’s body into the boot of their car. The wheelchair sat abandoned in a corner, with my clothes tossed over its dark-blue plastic back-rest. Before the last white coat left the room I signalled my wish to have the TV turned on low. On screen was my father’s favourite quiz show, Letters and Numbers. Since daybreak an unremitting drizzle had been streaking the windows.

- 华研外语 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...