如何读为什么读 英文原版书籍 How to Read and Why 英美文学导读 英文版 进口原版英文书

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 12 件 |

商品详情

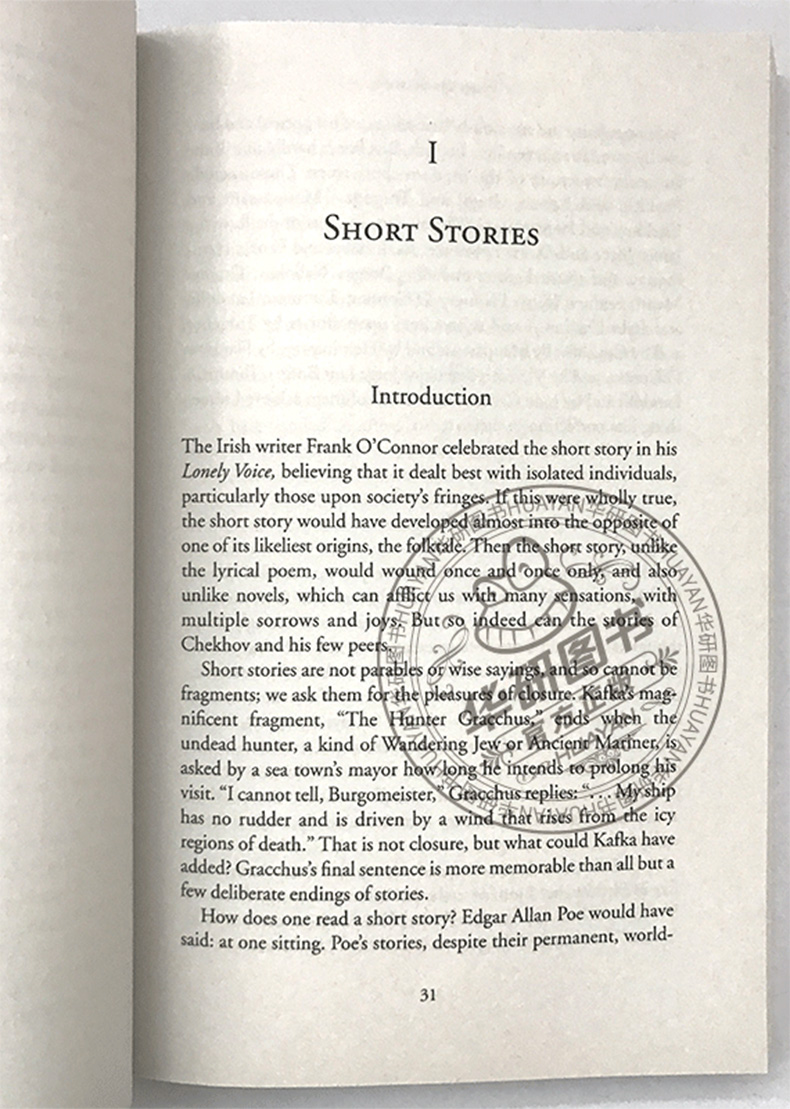

书名:How to Read and Why 如何读,为什么读

作者:Harold Bloom哈罗德·布鲁姆

出版社名称:Touchstone

出版时间:2001

语种:英文

ISBN:9780684859071

商品尺寸:14 x1.8 x 21.3 cm

包装:平装

页数:286

如何善于读书,没有单一的途径,不过,为什么应当读书,却有一个主要的理由。我们可获取的资讯是无穷的;哪里可以找到智慧?如果你幸运,你会碰到某个老师,他可以帮助你,然而你终究是孤单的,独自继续下去而没有更多中介。善于读书是孤独可以提供给你的极大乐趣之一。

How to Read and Why《如何读,为什么读》是布鲁姆在年近古稀时出版的一本个人化的导读著作,这位阅读大师、智慧老人、经典的经典读者为我们正本清源,梳理西方不朽作品,谈论他从童年到晚年喜爱的诗、小说、戏剧。《如何读,为什么读》可以说是《西方正典》的互补版,已读过《西方正典》的读者,可在这里再探索和再发现西方正典,以及再接受布鲁姆的批评能量;初次接触布鲁姆的读者,则可从这里开始,踏上寻访和分享西方正典的旅程。

本书是英文原版,文字通俗,术语相对少。在这个网络当道、文学式微的年代,布鲁姆针对新世纪的读者,提出了要读好的一流作品的文学理念,说明了这些作品妙在哪里,为何要读这些作品、要如何读才能得其精髓。本书适合英美文学学习者、研究者和爱好者阅读。

媒体评论:

“他是批评界的巨人……他对文学的热忱是一种令人陶醉的麻醉剂。”——《纽约时报杂志》

“读哈罗德·布鲁姆的评论……就好像在读石火电闪般的经典。”——M.H.艾布拉姆斯

“哈罗德·布鲁姆是我们时代文学批评界的领军人物……他激活了他的文学批评,将自己的满腔热情倾注其中。”——《卫报》

“Information is endlessly available to us; where shall wisdom be found?” is the crucial question with which renowned literary critic Harold Bloom begins this impassioned book on the pleasures and benefits of reading well. For more than forty years, Bloom has transformed college students into lifelong readers with his unrivaled love for literature. Now, at a time when faster and easier electronic media threatens to eclipse the practice of reading, Bloom draws on his experience as critic, teacher, and prolific reader to plumb the great books for their sustaining wisdom.

Shedding all polemic, Bloom addresses the solitary reader, who, he urges, should read for the purest of all reasons: to discover and augment the self. His ultimate faith in the restorative power of literature resonates on every page of this infinitely rewarding and important book.

Review:

“Superb... A wonderful, entertaining book...extraordinarily wise, nourishing, and beautiful. ” —Michael Pakenham, The Baltimore Sun

“Harold Bloom is one of the great literary critics of his time...How to Read and Why is... the testament of a veteran. ” —John Sutherland, The Washington Post Book World

“Bloom is one of the last... of his kind... one of the greatest educators of our time...Wonderful... Bloom writes with passion of those writers whom he loves, and whose work for him affirms life. ” —John Banville, The Irish Times

How to Read and Why《如何读,为什么读》教你如何读和为什么读,书中用众多的样本和例子来示范:短诗或长诗;短篇小说、长篇小说和戏剧。

Harold Bloom’s urgency in How to Read and Why may have much to do with his age. He brackets his combative, inspiring manual with the news that he is nearing 70 and hasn’t time for the mediocre. (One doubts that he ever did.) Nor will he countenance such fashionable notions as the death of the author or abide “the vagaries of our current counter-Puritanism” let alone “ideological cheerleading.” Successively exploring the short story, poetry, the novel, and drama, Bloom illuminates both the how and why of his title and points us in all the right directions: toward the Romantics because they “startle us out of our sleep-of-death into a more capacious sense of life”; toward Austen, James, Proust; toward Thomas Mann, Toni Morrison, and Cormac McCarthy; toward Cervantes and Shakespeare (but of course!), Ibsen and Oscar Wilde.

How should we read? Slowly, with love, openness, and with our inner ear cocked. Then we should reread, reread, reread, and do so aloud as often as possible. “As a boy of eight,” he tells us, “I would walk about chanting Housman’s and William Blake’s lyrics to myself, and I still do, less frequently yet with undiminished fervor.” And why should we engage in this apparently solitary activity? To increase our wit and imagination, our sense of intimacy—in short, our entire consciousness—and also to heal our pain. “Until you become yourself,” Bloom avers, “what benefit can you be to others.” So much for reading as an escape from the self!

Still, many of this volume’s pleasures may indeed be selfish. The author is at his best when he is thinking aloud and anew, and his material offers him—and therefore us—endless opportunities for discovery. Bloom cherishes poetry because it is “a prophetic mode” and fiction for its wisdom. Intriguingly, he fears more for the fate of the latter: “Novels require more readers than poems do, a statement so odd that it puzzles me, even as I agree with it.” We must, he adjures, crusade against its possible extinction and read novels “in the coming years of the third millennium, as they were read in the eighteenth and nineteenth century: for aesthetic pleasure and for spiritual insight.”

Bloom is never heavy, since his vision quest contains a healthy love of irony--Jedediah Purdy, take note: “Strip irony away from reading, and it loses at once all discipline and all surprise.” And this supreme critic makes us want to equal his reading prowess because he writes as well as he reads; his epigrams are equal to his opinions. He is also a master allusionist and quoter. His section on Hedda Gabler is preceded by three extraordinary statements, two from Ibsen, who insists, “There must be a troll in what I write.” Who would not want to proceed? Of course, Bloom can also accomplish his goal by sheer obstinacy. As far as he is concerned, Don Quixote may have been the first novel but it remains to this day the best one. Is he perhaps tweaking us into reading this gigantic masterwork by such bald overstatement? Bloom knows full well that a prophet should stop at nothing to get his belief and love across, and throughout How to Read and Why he is as unstinting as the visionary company he adores.

哈罗德·布鲁姆(1930-),当代美国知名文学教授、“耶鲁学派”批评家、文学理论家。曾执教于耶鲁大学、纽约大学和哈佛大学等知名高校。主要研究领域包括诗歌批评、理论批评和宗教批评三大方面,代表作有《影响的焦虑》(1973)、《误读之图》(1975)、《西方正典》(1994)、《莎士比亚:人的发明》(1998)等,以其独特的理论建构和批评实践被誉为“西方传统中极有天赋、有原创性和有煽动性的一位文学批评家”。

Harold Bloom is Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University, Berg Professor of English at New York University, and a former Charles Eliot Norton Professor at Harvard. His more than twenty books include Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, The Western Canon, The Book of J, and his most recent work, Stories and Poems for Extremely Intelligent Children of All Ages. He is a MacArthur Prize fellow; a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters; the recipient of many awards, including the Academy’s Gold Medal for Criticism; and he holds honorary degrees from the universities of Rome and Bologna.

Preface

Prologue: Why Read?

I. Short Stories

Introduction

Ivan Turgenev

“Bezhin Lea”

“Kasyan from the Beautiful Lands”

Anton Chekhov

“The Kiss”

“TheStudent”

“The Lady with the Dog”

Guy de Maupassant

“Madame Tellier’s Establishment”

“The Horla”

Ernest Hemingway

“Hills Like White Elephants”

“Good Rest You Merry, Gentlemen”

“TheSnows of Kilimanjaro”

“A Sea Change”

Flannery O’Connor

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find”

“Good Country People”

“A View of the Woods”

Vladimir Nabokov

“The Vane Sisters”

Jorge Luis Borges

“Tlon, Ugbar, Orbis Tertius”

Tommaso Landolfi

“Gogol’s Wife”

Italo Calvino

“Invisible Cities”

Summary Observations

II. Poems

Introduction

Housman, Blake, Landor, and Tennyson

A. E. Housman

“Into My Heart an Air That Kills”

William Blake

“TheSick Rose”

Walter Savage Landor

“On His Seventy-fifth Birthday”

Alfred Lord Tennyson

“The Eagle”

“Ulysses”

Robert Browning

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”

Walt Whitman

Song of Myself

Dickinson, Bronte, Popular Ballads, and“Tom O’Bedlam”

Emily Dickinson

Poem 1260,“BecauseThat You Are Going”

Emily Bronte

“Stanzas: Often Rebuked, Yet Always Back Returning”

Popular Ballads

“Sir Patrick Spence”

“The Unquiet Grave”

Anonymous

“Tom O’Bedlam”

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 121,“'TisBetter toBe Vile Than Vile Esteemed”

Sonnet 129,“Th’Expense of Spirit in a Waste of Shame”

Sonnet 121,“Two Loves I Have, of Comfort and Despair”

John Milton

Paradise Lost

William Wordsworth

“A Slumber Did my Spirit Seal”

“My Heart Leaps Up When I Behold”

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Shelly and Keats

Percy Bysshe Shelley

The Triumph of Life

John Keats

“La Belle Dame Sans Merci”

Summary Observations

III. Novels, Part I

Introduction

Miguel de Cervantes:Don Quixote

Stendhal:The Charterhouse of Parma

Jane Austen:Emma

Charles Dickens:Great Expectations

Fyodor Dostoevsky:Crime and Punishment

Henry James:The Portrait of a Lady

Marcel Proust:In Search of Lost Time

Thomas Mann:The Magic Mountain

Summary Observations

IV. Plays

Introduction

William Shakespeare:Hamlet

Henrik Ibsen:Hedda Gabler

Oscar Wilde:The Importance of Being Earnest

Summary Observations

V. Novels, Part II

Herman Melville:Moby-Dick

William Faulkner:As I Lay Dying

Nathanael West:Miss Lonelyhearts

Thomas Pynchon:The Crying of Lot 49

Cormac McCarthy:Blood Meridian

Ralph Ellison:Invisible Man

Toni Morrison:Song of Solomon

Summary Observations

Epilogue: Completing the Work

Prologue: Why Read?

It matters, if individuals are to retain any capacity to form their own judgments and opinions, that they continue to read for themselves. How they read, well or badly, and what they read, cannot depend wholly upon themselves, but why they read must be for and in their own interest. You can read merely to pass the time, or you can read with an overt urgency, but eventually you will read against the clock. Bible readers, those who search the Bible for themselves, perhaps exemplify the urgency more plainly than readers of Shakespeare, yet the quest is the same. One of the uses of reading is to prepare ourselves for change, and the final change alas is universal.

I turn to reading as a solitary praxis, rather than as an educational enterprise. The way we read now, when we are alone with ourselves, retains considerable continuity with the past, however it is performed in the academies. My ideal reader (and lifelong hero) is Dr. Samuel Johnson, who knew and expressed both the power and the limitation of incessant reading. Like every other activity of the mind, it must satisfy Johnson’s prime concern, which is with “what comes near to ourself, what we can put to use.” Sir Francis Bacon, who provided some of the ideas that Johnson put to use, famously gave the advice: “Read not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted, nor to find talk and discourse, but to weigh and consider.” I add to Bacon and Johnson a third sage of reading, Emerson, fierce enemy of history and of all historicisms, who remarked that the best books “impress us with the conviction, that one nature wrote and the same reads.” Let me fuse Bacon, Johnson, and Emerson into a formula of how to read: find what comes near to you that can be put to the use of weighing and considering, and that addresses you as though you share the one nature, free of time’s tyranny. Pragmatically that means, first find Shakespeare, and let him find you. If King Lear is fully to find you, then weigh and consider the nature it shares with you; its closeness to yourself. I do not intend this as an idealism, but as a pragmatism. Putting the tragedy to use as a complaint against patriarchy is to forsake your own prime interests, particularly as a young woman, which sounds rather more ironical than it is. Shakespeare, more than Sophocles, is the inescapable authority upon intergenerational conflict, and more than anyone else, upon the differences between women and men. Be open to a full reading of King Lear, and you will understand better the origins of what you judge to be patriarchy.

Ultimately we read—as Bacon, Johnson, and Emerson agree—in order to strengthen the self, and to learn its authentic interests. We experience such augmentations as pleasure, which may be why aesthetic values have always been deprecated by social moralists, from Plato through our current campus Puritans. The pleasures of reading indeed are selfish rather than social. You cannot directly improve anyone else’s life by reading better or more deeply. I remain skeptical of the traditional social hope that care for others may be stimulated by the growth of individual imagination, and I am wary of any arguments whatsoever that connect the pleasures of solitary reading to the public good.

The sorrow of professional reading is that you recapture only rarely the pleasure of reading you knew in youth, when books were a Hazlittian gusto. The way we read now partly depends upon our distance, inner or outer, from the universities, where reading is scarcely taught as a pleasure, in any of the deeper senses of the aesthetics of pleasure. Opening yourself to a direct confrontation with Shakespeare at his strongest, as in King Lear, is never an easy pleasure, whether in youth or in age, and yet not to read King Lear fully (which means without ideological expectations) is to be cognitively as well as aesthetically defrauded. A childhood largely spent watching television yields to an adolescence with a computer, and the university receives a student unlikely to welcome the suggestion that we must endure our going hence even as our going hither: ripeness is all. Reading falls apart, and much of the self scatters with it. All this is past lamenting, and will not be remedied by any vows or programs. What is to be done can only be performed by some version of elitism, and that is now unacceptable, for reasons both good and bad. There are still solitary readers, young and old, everywhere, even in the universities. If there is a function of criticism at the present time, it must be to address itself to the solitary reader, who reads for herself, and not for the interests that supposedly transcend the self.

Value, in literature as in life, has much to do with the idiosyncratic, with the excess by which meaning gets started. It is not accidental that historicists—critics who believe all of us to be overdetermined by societal history—should also regard literary characters as marks upon a page, and nothing more. Hamlet is not even a case history if our thoughts are not at all our own. I come then to the first principle if we are to restore the way we read now, a principle I appropriate from Dr. Johnson: Clear your mind of cant. Your dictionary will tell you that cant in this sense is speech overflowing with pious platitudes, the peculiar vocabulary of a sect or coven. Since the universities have empowered such covens as “gender and sexuality” and “multiculturalism,” Johnson’s admonition thus becomes “Clear your mind of academic cant.” A university culture where the appreciation of Victorian women’s underwear replaces the appreciation of Charles Dickens and Robert Browning sounds like the outrageousness of a new Nathanael West, but is merely the norm. A side product of such “cultural poetics” is that there can be no new Nathanael West, for how could such an academic culture sustain parody? The poems of our climate have been replaced by the body stockings of our culture. Our new Materialists tell us that they have recovered the body for historicism, and assert that they work in the name of the Reality Principle. The life of the mind must yield to the death of the body, yet that hardly requires the cheerleading of an academic sect.

Clear your mind of cant leads on to the second principle of restoring reading: Do not attempt to improve your neighbor or your neighborhood by what or how you read. Self-improvement is a large enough project for your mind and spirit: there are no ethics of reading. The mind should be kept at home until its primal ignorance has been purged; premature excursions into activism have their charm, but are time-consuming, and for reading there will never be enough time. Historicizing, whether of past or present, is a kind of idolatry, an obsessive worship of things in time. Read therefore by the inner light that John Milton celebrated and that Emerson took as a principle of reading, which can be our third: A scholar is a candle which the love and desire of all men will light. Wallace Stevens, perhaps forgetting his source, wrote marvelous variations upon that metaphor, but the original Emersonian phrasing makes for a clearer statement of the third principle of reading. You need not fear that the freedom of your development as a reader is selfish, because if you become an authentic reader, then the response to your labors will confirm you as an illumination to others. I ponder the letters that I receive from strangers these last seven or eight years, and generally I am too moved to reply. Their pathos, for me, is that all too often they testify to a yearning for canonical literary study that universities disdain to fulfill. Emerson said that society cannot do without cultivated men and women, and prophetically he added: “The people, and not the college, is the writer’s home.” He meant strong writers, representative men and women, who represented themselves, and not constituencies, since his politics were those of the spirit.

The largely forgotten function of a university education is caught forever in Emerson’s address “The American Scholar,” when he says of the scholar’s duties: “They may all be comprised in self-trust.” I take from Emerson also my fourth principle of reading: One must be an inventor to read well. ”Creative reading” in Emerson’s sense I once named as “misreading,” a word that persuaded opponents that I suffered from a voluntary dyslexia. The ruin or blank that they see when they look at a poem is in their own eye. Self-trust is not an endowment, but is the Second Birth of the mind, which cannot come without years of deep reading. There are no absolute standards for the aesthetic. If you wish to maintain that Shakespeare’s ascendancy was a product of colonialism, then who will bother to confute you? Shakespeare after four centuries is more pervasive than ever he was before; they will perform him in outer space, and on other worlds, if those worlds are reached. He is not a conspiracy of Western culture; he contains every principle of reading, and he is my touchstone throughout this book. Borges attributed this universalism to Shakespeare’s apparent selflessness, but that quality is a large metaphor for Shakespeare’s difference, which finally is cognitive power as such. We read, frequently if unknowingly, in quest of a mind more original than our own.

Since ideology, particularly in its shallower versions, is peculiarly destructive of the capacity to apprehend and appreciate irony, I suggest that the recovery of the ironic might be our fifth principle for the restoration of reading. Think of the endless irony of Hamlet, who when he says one thing almost invariably means another, frequently indeed the opposite of what he says. But with this principle, I am close to despair, since you can no more teach someone to be ironic than you can instruct them to become solitary. And yet the loss of irony is the death of reading, and of what had been civilized in our natures.

- 华研外语 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...