永生的海拉 英文原版书 The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks 不朽的生命 HBO同名电影原著 英文版进口书籍正版

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 49 件 |

商品详情

书名:The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks 永生的海拉

作者:Rebecca Skloot

出版社名称:Crown

出版时间:2011

语种:英语

ISBN:9781400052189

商品尺寸:18.8 x 8.4 x 26.1 cm

包装:平装

★本书荣获亚马逊网站2010年度编辑选书

★本书荣获亚马逊网站2010年度编辑选书

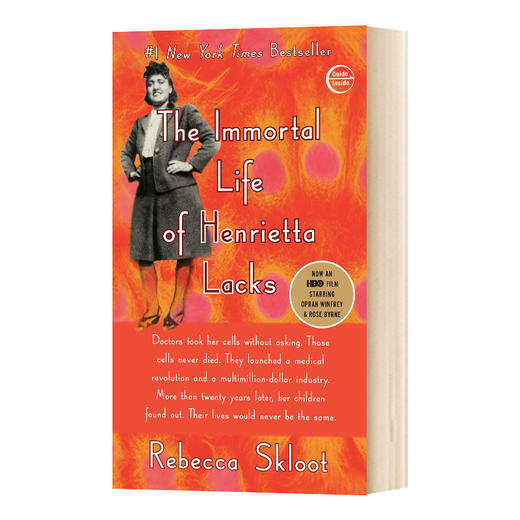

★芝加哥论坛报核心书奖(非文学类) ★被美国《纽约时报》、《华盛顿邮报》等60多家媒体评为年度好书 ★雄踞《纽约时报》畅销书排行榜一年 ★美国著名脱口秀主持人奥普拉心仪之作,携手HBO制作拍摄同名电影 ★她的故事打动地球上每一个人 她叫海瑞塔•拉克斯,科学家们都叫她”海拉”。 她是黑人,美国南方的贫穷烟农。她死于子宫癌,肿瘤细胞被医生取走,成为医学史上很早经人工培养而“永生不死”的细胞。但是她和家人却毫不知情。 海拉细胞是研发小儿麻痹疫苗的功臣,协助科学家解开癌症、病毒和原子弹效应的奥秘,促成试管婴儿、基因复制、基因图谱的重要发展,并造就了总价值超过几十亿美元的人体生物材料产业。现在,海拉细胞已经繁衍的总重量相当于100座帝国大厦,可以铺满整个地球。 然而60年来,海瑞塔•拉克斯被埋在毫不起眼的墓地里,她的家人没有享受到细胞带来的任何利益,甚至在她死后几十年后,她的女儿才得知母亲细胞的事:科学家一直在复制母亲?拿母亲的细胞做实验?既然母亲对现代医学如此重要,为什么她的孩子们连医疗保险都付不起? The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks《永生的海拉》作者美国科普作家丽贝卡•思科鲁特耗时十年挖掘这段精彩的历史,记述拉克斯一家与“海拉”细胞的名声毫不匹配的生活,与此同时,也揭开了人体实验的黑暗过去,并探讨了医学伦理以及身体组织所有权的法律问题,《永生的海拉》中所涉及的种族和信仰问题同样因为真实而动人心魄。 媒体推荐 “这本书让我爱不释手……这是一个关于现代医学、生命伦理学,以及种族关系的故事,优美、感人。——《娱乐周刊》 “科普作品通常只是阐述那些“事实”。而这本思科鲁特的处女作,则更加深刻、大胆、更加神奇。——《纽约评论家》 《永生的海拉》是科普作品的一个胜利……这是我读过的很好的非虚构类图书之一。——wired.com网站 这是一份调查报告,以灵巧的文笔阐述了由医学成就而导致的一场社会性不公,以及由此产生的科学与医学界的奇迹。——《华盛顿邮报》 非常动人……一个精心打造的首次亮相。——《芝加哥太阳报》 Now a major motion picture from HBO® starring Oprah Winfrey and Rose Byrne. Her name was Henrietta Lacks, but scientists know her as HeLa. She was a poor Southern tobacco farmer who worked the same land as her slave ancestors, yet her cells—taken without her knowledge—became one of the most important tools in medicine. The first “immortal” human cells grown in culture, they are still alive today, though she has been dead for more than sixty years. If you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—as much as a hundred Empire State Buildings. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine; uncovered secrets of cancer, viruses, and the atom bomb’s effects; helped lead to important advances like in vitro fertilization, cloning, and gene mapping; and have been bought and sold by the billions. Yet Henrietta Lacks remains virtually unknown, buried in an unmarked grave. Now Rebecca Skloot takes us on an extraordinary journey, from the “colored” ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to stark white laboratories with freezers full of HeLa cells; from Henrietta’s small, dying hometown of Clover, Virginia—a land of wooden slave quarters, faith healings, and voodoo—to East Baltimore today, where her children and grandchildren live and struggle with the legacy of her cells. Henrietta’s family did not learn of her “immortality” until more than twenty years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. And though the cells had launched a multimillion-dollar industry that sells human biological materials, her family never saw any of the profits. As Rebecca Skloot so brilliantly shows, the story of the Lacks family—past and present—is inextricably connected to the dark history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of bioethics, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we are made of. Over the decade it took to uncover this story, Rebecca became enmeshed in the lives of the Lacks family—especially Henrietta’s daughter Deborah, who was devastated to learn about her mother’s cells. She was consumed with questions: Had scientists cloned her mother? Did it hurt her when researchers infected her cells with viruses and shot them into space? What happened to her sister, Elsie, who died in a mental institution at the age of fifteen? And if her mother was so important to medicine, why couldn’t her children afford health insurance? Intimate in feeling, astonishing in scope, and impossible to put down, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks captures the beauty and drama of scientific discovery, as well as its human consequences.

丽贝卡·思科鲁特,现居芝加哥。美国著名科普作家,美国国家公共电台与美国公共电视网“科学新星”频道的记者,《大众科学》杂志的特约编辑。曾任美国国家图书评论会副主席,在孟菲斯大学、匹兹堡大学,纽约大学等多所大学教授课程。 《永生的海拉》已被翻译成二十多种外语,并被美国HBO频道改编为电影。 Rebecca Skloot is an award-winning science writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine; O, The Oprah Magazine; Discover; and many others. She is coeditor of The Best American Science Writing 2011 and has worked as a correspondent for NPR’s Radiolab and PBS’s Nova ScienceNOW. She was named one of five surprising leaders of 2010 by the Washington Post. Skloot's debut book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, took more than a decade to research and write, and instantly became a New York Times bestseller. It was chosen as a best book of 2010 by more than sixty media outlets, including Entertainment Weekly, People, and the New York Times. It is being translated into more than twenty-five languages, adapted into a young reader edition, and being made into an HBO film produced by Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball. Skloot is the founder and president of The Henrietta Lacks Foundation. She has a B.S. in biological sciences and an MFA in creative nonfiction. She has taught creative writing and science journalism at the University of Memphis, the University of Pittsburgh, and New York University. She lives in Chicago. For more information, visit her website at RebeccaSkloot.com, where you’ll find links to follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

丽贝卡·思科鲁特,现居芝加哥。美国著名科普作家,美国国家公共电台与美国公共电视网“科学新星”频道的记者,《大众科学》杂志的特约编辑。曾任美国国家图书评论会副主席,在孟菲斯大学、匹兹堡大学,纽约大学等多所大学教授课程。 《永生的海拉》已被翻译成二十多种外语,并被美国HBO频道改编为电影。 Rebecca Skloot is an award-winning science writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine; O, The Oprah Magazine; Discover; and many others. She is coeditor of The Best American Science Writing 2011 and has worked as a correspondent for NPR’s Radiolab and PBS’s Nova ScienceNOW. She was named one of five surprising leaders of 2010 by the Washington Post. Skloot's debut book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, took more than a decade to research and write, and instantly became a New York Times bestseller. It was chosen as a best book of 2010 by more than sixty media outlets, including Entertainment Weekly, People, and the New York Times. It is being translated into more than twenty-five languages, adapted into a young reader edition, and being made into an HBO film produced by Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball. Skloot is the founder and president of The Henrietta Lacks Foundation. She has a B.S. in biological sciences and an MFA in creative nonfiction. She has taught creative writing and science journalism at the University of Memphis, the University of Pittsburgh, and New York University. She lives in Chicago. For more information, visit her website at RebeccaSkloot.com, where you’ll find links to follow her on Twitter and Facebook.  PROLOGUE The Woman in the Photograph There’s a photo on my wall of a woman I’ve never met, its left corner torn and patched together with tape. She looks straight into the camera and smiles, hands on hips, dress suit neatly pressed, lips painted deep red. It’s the late 1940s and she hasn’t yet reached the age of thirty. Her light brown skin is smooth, her eyes still young and playful, oblivious to the tumor growing inside her—a tumor that would leave her five children motherless and change the future of medicine. Beneath the photo, a caption says her name is “Henrietta Lacks, Helen Lane or Helen Larson.” No one knows who took that picture, but it’s appeared hundreds of times in magazines and science textbooks, on blogs and laboratory walls. She’s usually identified as Helen Lane, but often she has no name at all. She’s simply called HeLa, the code name given to the world’s first immortal human cells—her cells, cut from her cervix just months before she died. Her real name is Henrietta Lacks. I’ve spent years staring at that photo, wondering what kind of life she led, what happened to her children, and what she’d think about cells from her cervix living on forever—bought, sold, packaged, and shipped by the trillions to laboratories around the world. I’ve tried to imagine how she’d feel knowing that her cells went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to human cells in zero gravity, or that they helped with some of the most important advances in medicine: the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization. I’m pretty sure that she—like most of us—would be shocked to hear that there are trillions more of her cells growing in laboratories now than there ever were in her body. There’s no way of knowing exactly how many of Henrietta’s cells are alive today. One scientist estimates that if you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—an inconceivable number, given that an individual cell weighs almost nothing. Another scientist calculated that if you could lay all HeLa cells ever grown end-to-end, they’d wrap around the Earth at least three times, spanning more than 350 million feet. In her prime, Henrietta herself stood only a bit over five feet tall. I first learned about HeLa cells and the woman behind them in 1988, thirty-seven years after her death, when I was sixteen and sitting in a community college biology class. My instructor, Donald Defler, a gnomish balding man, paced at the front of the lecture hall and flipped on an overhead projector. He pointed to two diagrams that appeared on the wall behind him. They were schematics of the cell reproduction cycle, but to me they just looked like a neon-colored mess of arrows, squares, and circles with words I didn’t understand, like “MPF Triggering a Chain Reaction of Protein Activations.” I was a kid who’d failed freshman year at the regular public high school because she never showed up. I’d transferred to an alternative school that offered dream studies instead of biology, so I was taking Defler’s class for high-school credit, which meant that I was sitting in a college lecture hall at sixteen with words like mitosis and kinase inhibitors flying around. I was completely lost. “Do we have to memorize everything on those diagrams?” one student yelled. Yes, Defler said, we had to memorize the diagrams, and yes, they’d be on the test, but that didn’t matter right then. What he wanted us to understand was that cells are amazing things: There are about one hundred trillion of them in our bodies, each so small that several thousand could fit on the period at the end of this sentence. They make up all our tissues—muscle, bone, blood—which in turn make up our organs.

PROLOGUE The Woman in the Photograph There’s a photo on my wall of a woman I’ve never met, its left corner torn and patched together with tape. She looks straight into the camera and smiles, hands on hips, dress suit neatly pressed, lips painted deep red. It’s the late 1940s and she hasn’t yet reached the age of thirty. Her light brown skin is smooth, her eyes still young and playful, oblivious to the tumor growing inside her—a tumor that would leave her five children motherless and change the future of medicine. Beneath the photo, a caption says her name is “Henrietta Lacks, Helen Lane or Helen Larson.” No one knows who took that picture, but it’s appeared hundreds of times in magazines and science textbooks, on blogs and laboratory walls. She’s usually identified as Helen Lane, but often she has no name at all. She’s simply called HeLa, the code name given to the world’s first immortal human cells—her cells, cut from her cervix just months before she died. Her real name is Henrietta Lacks. I’ve spent years staring at that photo, wondering what kind of life she led, what happened to her children, and what she’d think about cells from her cervix living on forever—bought, sold, packaged, and shipped by the trillions to laboratories around the world. I’ve tried to imagine how she’d feel knowing that her cells went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to human cells in zero gravity, or that they helped with some of the most important advances in medicine: the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization. I’m pretty sure that she—like most of us—would be shocked to hear that there are trillions more of her cells growing in laboratories now than there ever were in her body. There’s no way of knowing exactly how many of Henrietta’s cells are alive today. One scientist estimates that if you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—an inconceivable number, given that an individual cell weighs almost nothing. Another scientist calculated that if you could lay all HeLa cells ever grown end-to-end, they’d wrap around the Earth at least three times, spanning more than 350 million feet. In her prime, Henrietta herself stood only a bit over five feet tall. I first learned about HeLa cells and the woman behind them in 1988, thirty-seven years after her death, when I was sixteen and sitting in a community college biology class. My instructor, Donald Defler, a gnomish balding man, paced at the front of the lecture hall and flipped on an overhead projector. He pointed to two diagrams that appeared on the wall behind him. They were schematics of the cell reproduction cycle, but to me they just looked like a neon-colored mess of arrows, squares, and circles with words I didn’t understand, like “MPF Triggering a Chain Reaction of Protein Activations.” I was a kid who’d failed freshman year at the regular public high school because she never showed up. I’d transferred to an alternative school that offered dream studies instead of biology, so I was taking Defler’s class for high-school credit, which meant that I was sitting in a college lecture hall at sixteen with words like mitosis and kinase inhibitors flying around. I was completely lost. “Do we have to memorize everything on those diagrams?” one student yelled. Yes, Defler said, we had to memorize the diagrams, and yes, they’d be on the test, but that didn’t matter right then. What he wanted us to understand was that cells are amazing things: There are about one hundred trillion of them in our bodies, each so small that several thousand could fit on the period at the end of this sentence. They make up all our tissues—muscle, bone, blood—which in turn make up our organs.

- 华研外语 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...