失联 认识沮丧重获自信 英文原版 心理学书籍 Lost Connections 抑郁焦虑的成因和改善方法 TED演讲者约翰哈里 英文版进口英语书

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 14 件 |

商品详情

书名:Lost Connections: Why You’re Depressed and How to Find Hope失联:认识沮丧,重获自信

书名:Lost Connections: Why You’re Depressed and How to Find Hope失联:认识沮丧,重获自信

作者:Johann Hari

出版社名称:Bloomsbury Publishing

出版时间:2019

语种:英文

ISBN:9781408878729

商品尺寸:12.6 x 2.2 x 19.8 cm

包装:平装

页数:336(以实物为准) ★改变你对抑郁的看法,那些不愉快的事,统统都要走开;

★改变你对抑郁的看法,那些不愉快的事,统统都要走开;

★甫出版登美国纽约时报、英国泰晤士报畅销排行榜;

★畅销书《追逐尖叫》作者、得奖记者约翰·哈里Johann Hari全新作品;

★大胆挑战我们今日对于精神疾病的认识!

半个多世纪以来,随着人们对于生理解剖、神经、内分泌等研究的日新月异,以及精神药物的推陈出新。今日对于忧郁症、焦虑症等精神疾病的主流思想是,这些疾患来自人体脑内化学平衡的失调。作者约翰·哈里从孩提时期被诊断出患有忧郁症,在这种强势的医学观点下,他从青少年时代开始便服用抗忧郁剂药物。

长大成人后,哈里立志要调查究竟这种对精神疾病的认识是否可信,随着各方社会学者的研究证据相继指出──忧郁症及焦虑并不是因为脑内化学不平衡所致,事实上,这些病症来自于我们当代的生活方式。在本书Lost Connections: Why You’re Depressed and How to Find Hope《失联:认识沮丧,重获自信》这趟壮阔的旅程里,哈里介绍了巴尔地摩的惊人研究、印地安那州的阿米什社群(Amish)、柏林…他整理出九个真正造成忧郁与焦虑的肇因,以及科学家发现的七个真正有效的改善方法。

一如在TED上目前已有超过八百万人次点阅的革命性演讲「你对上瘾的所有认知都是错的」,与在全球掀起革命的《追逐尖叫》,本书是对于当代十分普遍的心理困境─忧郁症与焦虑症─至关重要的重新认识。

THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER

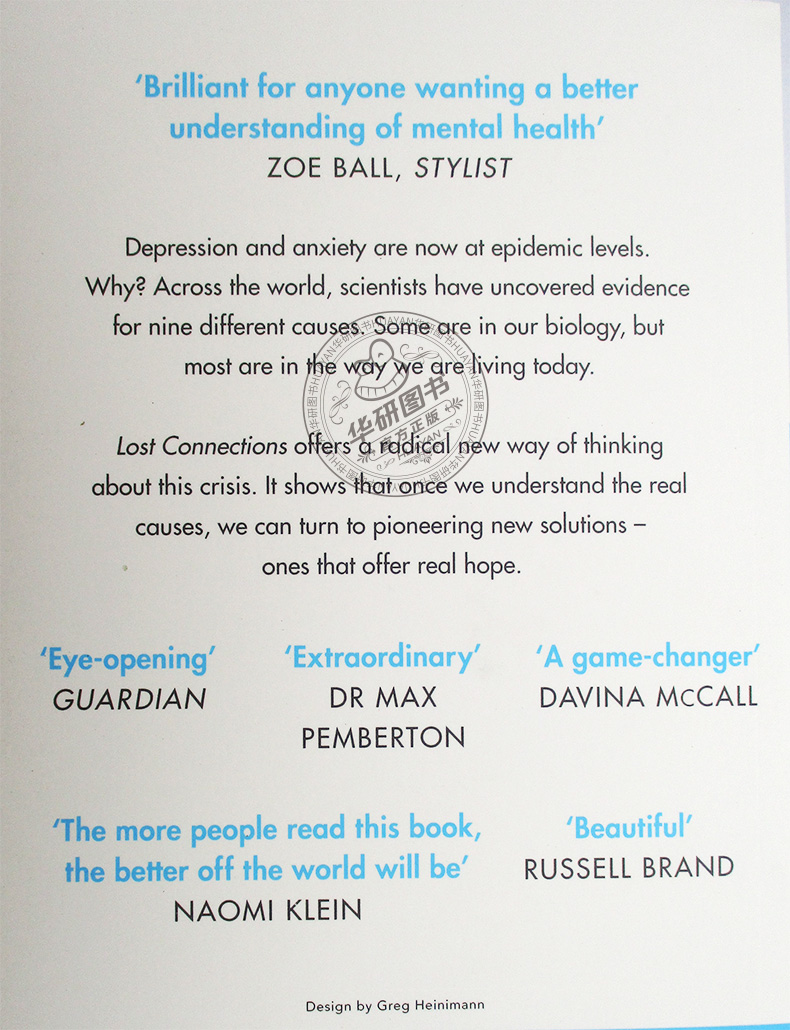

Depression and anxiety are now at epidemic levels. Why? Across the world, scientists have uncovered evidence for nine different causes. Some are in our biology, but most are in the way we are living today.

Lost Connections offers a radical new way of thinking about this crisis. It shows that once we understand the real causes, we can begin to turn to pioneering new solutions - ones that offer real hope.

Review

“If you have ever been down, or felt lost, this amazing book will change your life. Do yourself a favour - read it now”(Elton John)

“A brilliant, stimulating, radical take on mental health”(Matt Haig)

“A wonderful and incisive analysis”(Hillary Clinton)

“The more people read this book, the better off the world will be”(Naomi Klein)

“This book is a game changer”(Davina McCall)

“A prescient and compassionate Rosetta Stone for those trying to understand mental illness. Beautiful” (Russell Brand)

“As with his book on drugs, Johann Hari has delivered a remarkable tour de force on a difficult, complex and controversial subject and made the reader think anew”(Alastair Campbell) Johann Eduard Hari(born 21 January 1979) is a British writer and journalist who wrote columns for The Independent (London) and The Huffington Post and made contributions to other publications.

Johann Eduard Hari(born 21 January 1979) is a British writer and journalist who wrote columns for The Independent (London) and The Huffington Post and made contributions to other publications. The year after I swallowed my first antidepressant, Tipper Gore—the wife of Vice President Al Gore—explained to the newspaper USA Today why she had recently become depressed. “It was definitely a clinical depression, one that I was going to have to have help to overcome,” she said. “What I learned about is your brain needs a certain amount of serotonin and when you run out of that, it’s like running out of gas.” Tens of millions of people—including me—were being told the same thing.

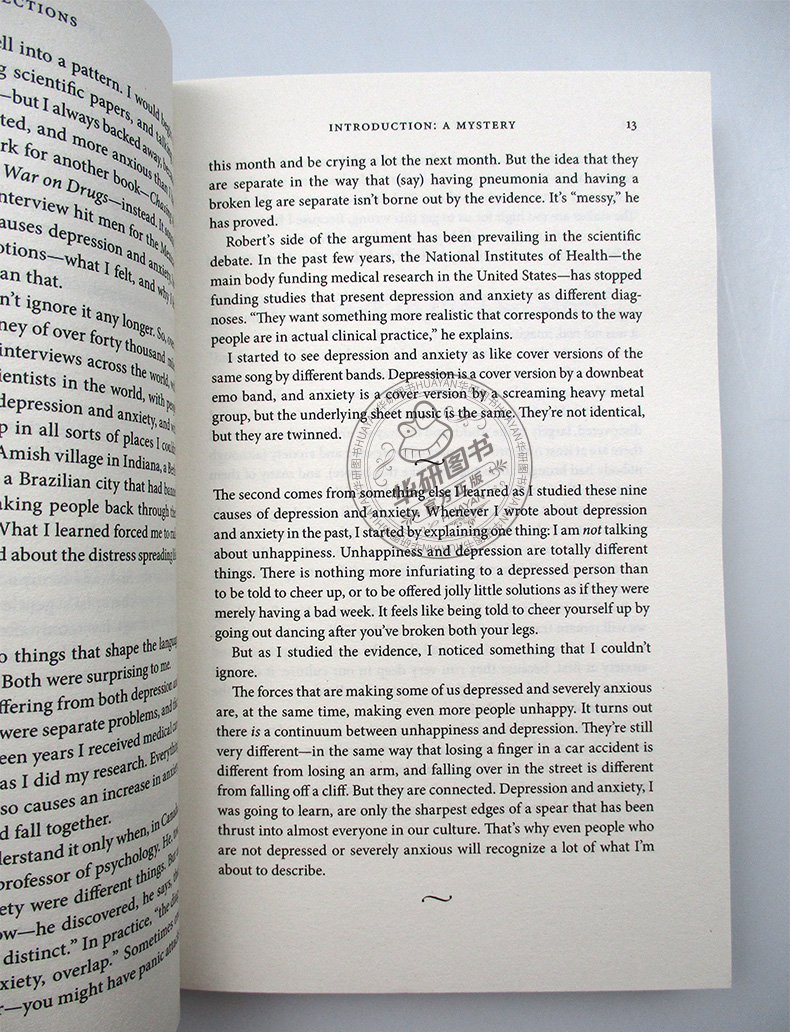

The year after I swallowed my first antidepressant, Tipper Gore—the wife of Vice President Al Gore—explained to the newspaper USA Today why she had recently become depressed. “It was definitely a clinical depression, one that I was going to have to have help to overcome,” she said. “What I learned about is your brain needs a certain amount of serotonin and when you run out of that, it’s like running out of gas.” Tens of millions of people—including me—were being told the same thing.

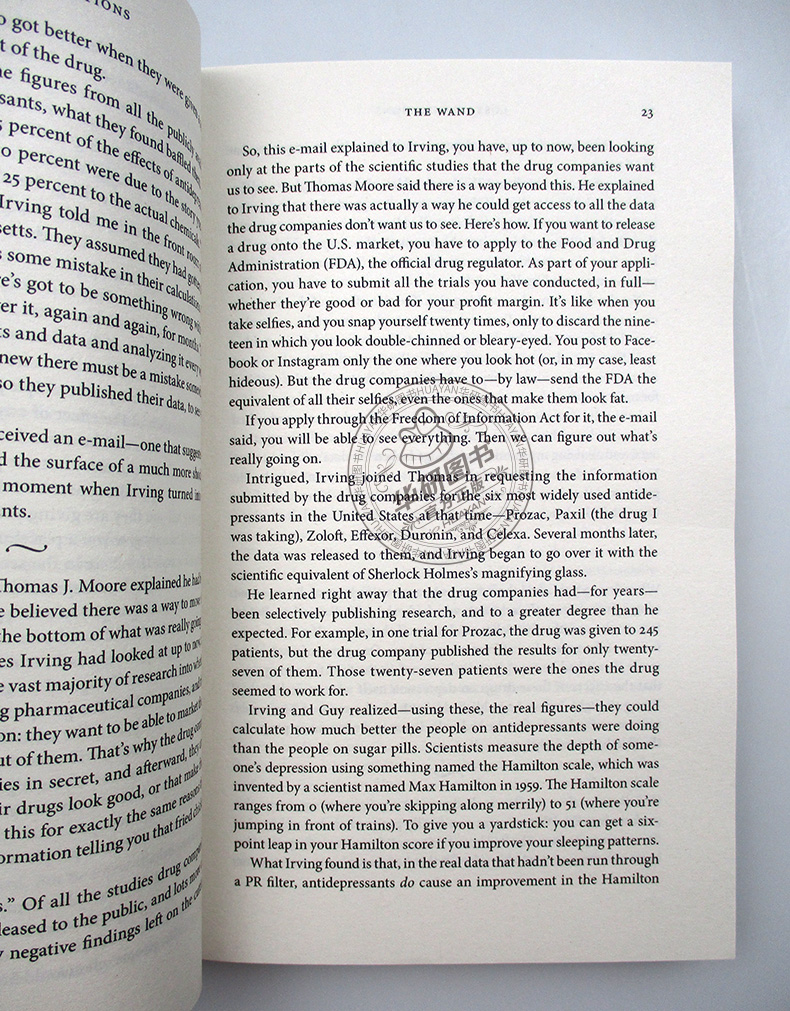

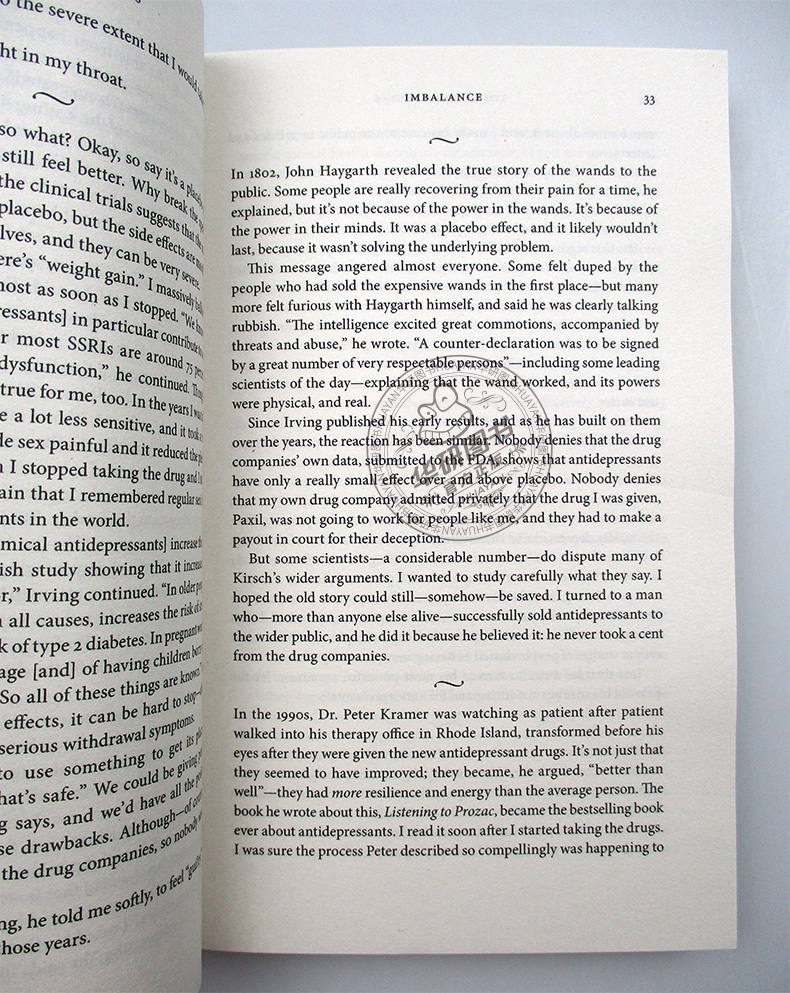

When Irving Kirsch discovered that these serotonin-boosting drugs were not having the effects that everyone was being sold, he began—to his surprise—to ask an even more basic question. What’s the evidence, he began to wonder, that depression is caused primarily by an imbalance of serotonin, or any other chemical, in the brain? Where did it come from?

The serotonin story began, Irving learned, quite by accident in a tuberculosis ward in New York City in the clammy summer of 1952, when some patients began to dance uncontrollably down a hospital corridior. A new drug named Marsilid had come along that doctors thought might help TB patients. It turned out it didn’t have much effect on TB—but the doctors noticed it did something else entirely. They could hardly miss it. It made the patients gleefully, joyfully euphoric—some began to dance frenetically.

So it wasn’t long before somebody decided, perfectly logically, to try to give it to depressed people—and it seemed to have a similar effect on them, for a short time. Not long after that, other drugs came along that seemed to have similar effects (also for short periods)—ones named Ipronid and Imipramine. So what, people started to ask, could these new drugs have in common? And whatever it was—could it hold the key to unlocking depression?

Nobody really knew where to look, and so for a decade the question hung in the air, tantalizing researchers. And then in 1965, a British doctor called Alec Coppen came up with a theory. What if, he asked, all these drugs were increasing levels of serotonin in the brain? If that were true, it would suggest that depression might be caused by low levels of serotonin. “It’s hard to overstate just how far out on a limb these scientists were climbing,” Dr. Gary Greenberg, who has written the history of this period, explains. “They really had no idea what serotonin was doing in the brain.” To be fair to the scientists who first put forward the idea, he says, they put it forward tentatively—as a suggestion. One of them said it was “at best a reductionist simplification,” and said it couldn’t be shown to be true “on the basis of data currently available.”

- 华研外语 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...