远离尘嚣 英文原版长篇小说 Far from the Madding Crowd 英文版进口书籍

| 运费: | ¥ 0.00-999.00 |

| 库存: | 42 件 |

商品详情

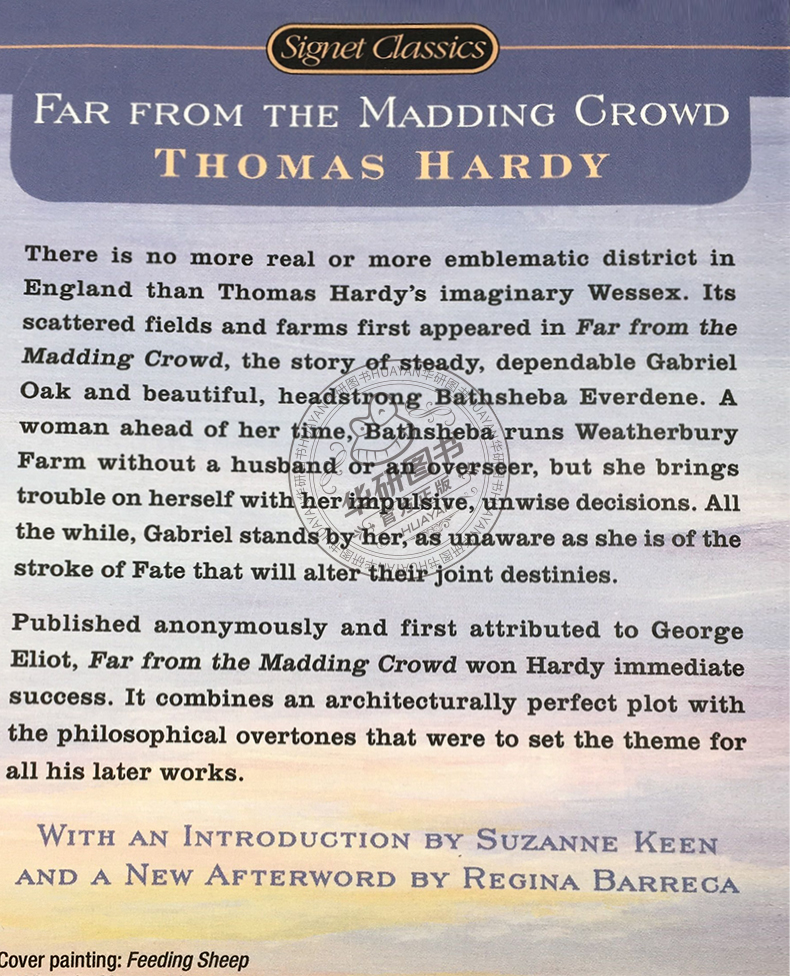

书名:Far from the Madding Crowd 远离尘嚣

难度:Lexile蓝思阅读指数1110

作者:Thomas Hardy托马斯·哈代

出版社名称:Signet Classics

出版时间:2002

语种:英文

ISBN:9780451531827

商品尺寸:10.7 x 2.7 x 17.2 cm

包装:简装

页数:400 (以实物为准)

Far from the Madding Crowd《远离尘嚣》是英国小说家托马斯·哈代的首部成功长篇,也开启了他此后以威塞克斯乡村为背景的优秀长篇小说系列。作品反映了资本主义发展在英国农村城镇的社会、经济、道德、人伦、风俗等方面所引起的深刻而剧烈的变化,表现了现存道德观念和法律制度与这一变化之间的冲突,以及处于这一变化冲突间的“威塞克斯乡民”的惶惑和抗争。

本版本为Signet Classics推出的简装便携全英文版原著,另外补充Suzanne Keen所作的序言,有助于理解作品及作者创作背景。

Thomas Hardy’s impassioned novel of courtship in rural life

Published anonymously and first attributed to George Eliot,Far from the Madding Crowd won Hardy immediate success. It combines an architecturally perfect plot with the philosophical overtones that were to set the theme for all his later works.

With an Introduction by Suzanne Keen

“Far from the Madding Crowd is the first of Thomas Hardy’s great novels, and the first to sound the tragic note for which his fiction is best remembered.” —Margaret Drabble

Far from the Madding Crowd《远离尘嚣》是英格兰伟大的小说家哈代的代表作。书中的主人公加布里埃尔经营着一个小农场,他对前来帮工的巴思喜巴小姐一见倾心,向她求婚却遭拒绝。一场突如其来的变故致使他倾家荡产,流落他乡。当他来到威瑟伯农场,他惊喜地发现农场主就是他朝思暮想的巴思喜巴小姐,不过这次他却成了巴思喜巴小姐的仆人。

There is no more real or more emblematic district in England than Thomas Hardy’s imaginary Wessex. Its scattered fields and farms first appeared inFar from the Madding Crowd, the story of steady, dependable Gabriel Oak and beautiful, headstrong Bathsheba runs Weatherbury Farm without a husband or an overseer, but she brings trouble on herself with herimpulsive, unwisedecisions. All the while, Gabriel stands by her, as unaware as she is of the stroke of Fatethat will alter their joint destinies.

托马斯·哈代(1840—1928),是英国小说家、诗人。他是横跨两个世纪的作家,早期和中期的创作以小说为主,继承和发扬了维多利亚时代的文学传统;晚期以出色的诗歌开拓了英国20世纪的文学。哈代起初写作诗歌,后因无缘发表,改事小说创作。1867—1868年完成第一部小说《穷人与贵妇》,但未能出版。首次发表的小说是《计出无奈》(1871),接着是《绿林荫下》(1872)、《一双湛蓝的眼睛》(1873),他的成名作是第四部小说《远离尘嚣》(1874)。一些评论家认为1878年发表的《还乡》是他非常出色的作品。他的另一部重要作品是《卡斯特桥市长》(1886);他很优秀的小说是《德伯家的苔丝》(1891);而《无名的裘德》(1896)却招致强烈的攻击,这使哈代发誓再不写小说,自此全力作诗,发表了《威塞克斯诗集》(1898)、《今昔诗篇》(1901)等8个诗集。此外还有《林地居民》(1887)等许多长篇小说和4个短篇小说集。哈代一生共发表了近20部长篇小说,其中著名的当推《德伯家的苔丝》《无名的裘德》《还乡》和《卡斯特桥市长》,诗8集共918首,此外,还有许多以“威塞克斯故事”为总名的中短篇小说,以及长篇史诗剧《列王》。

Thomas Hardy was born on June 2, 1840. In his writing, he immortalized the site of his birth—Egdon Heath, in Dorset, near Dorchester. Delicate as a child, he was taught at home by his mother before he attended grammar school. At sixteen, Hardy was apprenticed to an architect, and for many years, architecture was his profession; in his spare time, he pursued his first and last literary love, poetry. Finally convinced that he could earn his living as an author, he retired from architecture, married, and devoted himself to writing. An extremely productive novelist, Hardy published an important book every year or two. In 1896, disturbed by the public outcry over the unconventional subjects of his two greatest novels—Tess of the D’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure—he announced that he was giving up fiction and afterward produced only poetry. In later years, he received many honors. He died on January 11, 1928, and was buried in Poet’s Corner, in Westminster Abbey. It was as a poet that he wished to be remembered, but today critics regard his novels as his most memorable contribution to English literature for their psychological insight, decisive delineation of character, and profound presentation of tragedy.

Suzanne Keen, Professor of English at Washington and Lee University, is the author of two books on English fiction:Romances of the Archive in Contemporary British Fiction (2001) andVictorian Renovations of the Novel: Narrative Annexes and the Boundaries of Representation (1998). A recipient of Humanities for her academic work, she also reviews books forCommonweal magazine and serves as vice president of the Thomas Hardy Association.

When Farmer Oak smiled, the corners of his mouth spread till they were within an unimportant distance of his ears, his eyes were reduced to chinks, and diverging wrinkles appeared round them, extending upon his countenance like the rays in a rudimentary sketch of the rising sun.

His Christian name was Gabriel, and on working days he was a young man of sound judgment, easy motions, proper dress, and general good character. On Sundays he was a man of misty views, rather given to postponing, and hampered by his best clothes and umbrella: upon the whole, one who felt himself to occupy morally that vast middle space of Laodicean neutrality which lay between the Communion people of the parish and the drunken section,—that is, he went to church, but yawned privately by the time the congregation reached the Nicene creed, and thought of what there would be for dinner when he meant to be listening to the sermon. Or, to state his character as it stood in the scale of public opinion, when his friends and critics were in tantrums, he was considered rather a bad man; when they were pleased, he was rather a good man; when they were neither, he was a man whose moral colour was a kind of pepper-and-salt mixture.

Since he lived six times as many working-days as Sundays, Oak’s appearance in his old clothes was most peculiarly his own—the mental picture formed by his neighbours in imagining him being always dressed in that way. He wore a low-crowned felt hat, spread out at the base by tight jamming upon the head for security in high winds, and a coat like Dr. Johnson’s,4 his lower extremities being encased in ordinary leather leggings and boots emphatically large, affording to each foot a roomy apartment so constructed that any wearer might stand in a river all day long and know nothing of damp—their maker being a conscientious man who endeavoured to compensate for any weakness in his cut by unstinted dimension and solidity.

Mr. Oak carried about him, by way of watch, what may be called a small silver clock; in other words, it was a watch as to shape and intention, and a small clock as to size. This instrument being several years older than Oak’s grandfather, had the peculiarity of going either too fast or not at all. The smaller of its hands, too, occasionally slipped round on the pivot, and thus, though the minutes were told with precision, nobody could be quite certain of the hour they belonged to. The stopping peculiarity of his watch Oak remedied by thumps and shakes, and he escaped any evil consequences from the other two defects by constant comparisons with and observations of the sun and stars, and by pressing his face close to the glass of his neighbours’ windows, till he could discern the hour marked by the green-faced timekeepers within. It may be mentioned that Oak’s fob being difficult of access, by reason of its somewhat high situation in the waistband of his trousers (which also lay at a remote height under his waistcoat), the watch was as a necessity pulled out by throwing the body to one side, compressing the mouth and face to a mere mass of ruddy flesh on account of the exertion, and drawing up the watch by its chain, like a bucket from a well.

But some thoughtful persons, who had seen him walking across one of his fields on a certain December morning—sunny and exceedingly mild—might have regarded Gabriel Oak in other aspects than these. In his face one might notice that many of the hues and curves of youth had tarried on to manhood: there even remained in his remoter crannies some relics of the boy. His height and breadth would have been sufficient to make his presence imposing, had they been exhibited with due consideration. But there is a way some men have, rural and urban alike, for which the mind is more responsible than flesh and sinew: it is a way of curtailing their dimensions by their manner of showing them. And from a quiet modesty that would have become a vestal, which seemed continually to impress upon him that he had no great claim on the world’s room, Oak walked unassumingly, and with a faintly perceptible bend, yet distinct from a bowing of the shoulders. This may be said to be a defect in an individual if he depends for his valuation more upon his appearance than upon his capacity to wear well, which Oak did not.

He had just reached the time of life at which “young” is ceasing to be the prefix of “man” in speaking of one. He was at the brightest period of masculine growth, for his intellect and his emotions were clearly separated: he had passed the time during which the influence of youth indiscriminately mingles them in the character of impulse, and he had not yet arrived at the stage wherein they become united again, in the character of prejudice, by the influence of a wife and family. In short, he was twenty-eight, and a bachelor.

The field he was in this morning sloped to a ridge called Norcombe Hill. Through a spur of this hill ran the highway between Emminster and Chalk-Newton. Casually glancing over the hedge, Oak saw coming down the incline before him an ornamental spring waggon, painted yellow and gaily marked, drawn by two horses, a waggoner walking alongside bearing a whip perpendicularly. The waggon was laden with household goods and window plants, and on the apex of the whole sat a woman, young and attractive. Gabriel had not beheld the sight for more than half a minute, when the vehicle was brought to a standstill just beneath his eyes.

- 华研外语批发分销官方旗舰店 (微信公众号认证)

- 本店是“华研外语”品牌商自营店,全国所有“华研外语”、“华研教育”品牌图书都是我司出版发行的,本店为华研官方源头出货,所有图书均为正规正版,拥有实惠与正版的保障!!!

- 扫描二维码,访问我们的微信店铺

- 随时随地的购物、客服咨询、查询订单和物流...